When did a fact become a contradiction? The day I saw a roast chicken as charred remains of a dead animal, not as something delicious to eat. That day my fondness for food collided with my compassion for animals. That was fifty years ago, as a student learning how to cook French food and manage fancy restaurants. Instead of opting for work experience in a kitchen with haute cuisine, I spent the summer of 1973 employed in a chicken slaughterhouse.

Three years later, I was vegan, working at Compassion In World Farming and protesting against keeping chickens in battery cages too small to spread their wings, and pigs in stalls too narrow to turn around. Back in 1976, I was Compassion’s second full-time employee. The organisation’s notable growth from then to the present, now a pioneering international force for animals, reflects people’s growing interest in food and what happens to it before it is on their plates. But that interest hasn’t resulted in the end of eating animals. The annual global number of animals killed for food increased from almost eight billion in 1961 to more than 70 billion in 2020. More than 1.2 billion farmed animals are killed annually in the UK and 55 billion in the USA.

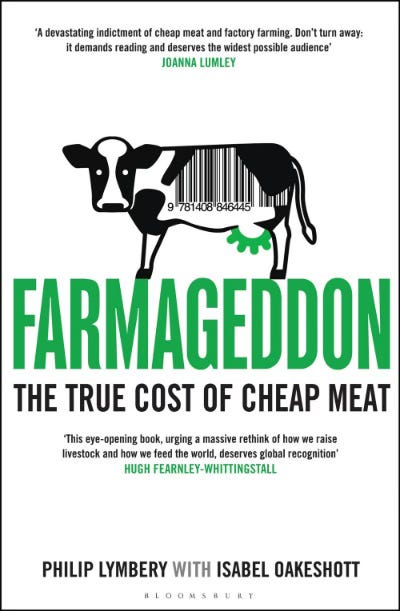

Philip Lymbery, Compassion’s Chief Executive, has written about how ‘a growing human population is in a furious competition for food with a burgeoning farm animal population’. We must rethink the overpopulation problem; eight billion people bring their issues. But seventy billion plus farmed animals present problems of an entirely different magnitude. Industrial agriculture, including intensive factory farming, is a significant cause of climate emergency. Animals raised for food are the real overpopulation problem. In Farmageddon: the true cost of cheap meat, Philip writes that ‘the global livestock industry already contributes 14.5 per cent of human-produced greenhouse gas emissions… more than all our cars, planes and trains put together.’

Fortunately, Compassion is not campaigning alone. There is a growing global movement of like-minded organisations seeking to improve animal welfare, protect the environment, end world hunger, stop climate emergency, and advance vegan living. I also welcome the emergence of companies developing plant-based meat and cultivated meat products. Consumers increasingly buy alternative products to meat, eggs, dairy, and leather manufactured from non-animal sources. Not everyone will go vegan like me, but many people will and already do live a near-vegan lifestyle. Food production causes as much as 37 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions, so this change in diet can be a tipping point for responding to the crisis appropriately.

Philip is the author of three books, Farmageddon, Dead Zone, and Sixty Harvests Left that are essential reading for understanding the link between animals and climate emergency. He also explains the negative impact of industrial agriculture on the environment, water, wildlife, human health, and animal welfare.

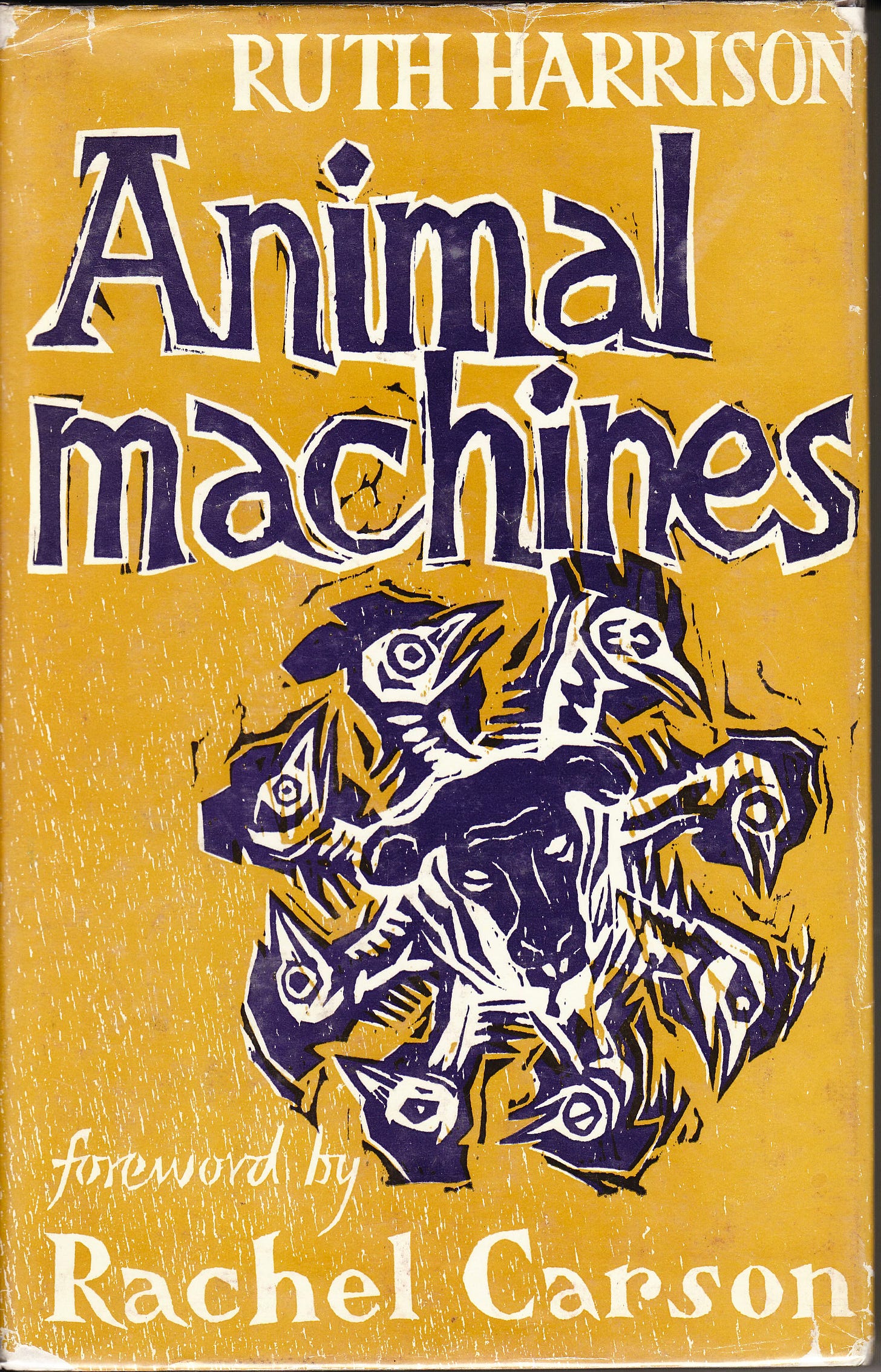

Two books inspired Philip to write. The first, Silent Spring is Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking book exposing the dangerous effects of chemicals used in farming in the countryside, first published in America in 1962. Two years later, Rachel wrote the foreword to Ruth Harrison’s Animal Machines, which foresaw the problems associated with industrial farming that Philip examines in his books. Reading Animal Machines prompted Peter and Anna Roberts, dairy farmers concerned with agriculture’s direction, to establish Compassion in 1967. For more about CIWF, read Roaming Wild: The Founding of Compassion In World Farming by Emma Silverthorn.

Philip’s first book, Farmageddon, questions the efficiency and efficacy of industrial farming. He asks if the ‘Farmageddon scenario—the death of our countryside, a scourge of disease and billions starving—[is] inevitable?’ There is no such thing as cheap meat. It comes with a hefty price, with our health and countryside at risk. Half of all antibiotics used worldwide (up to 80 per cent in the US) are routinely given to intensively farmed animals. Increasing amounts of land used to grow soya and grain for cattle in feedlots, sows in stalls, and chickens in cages, take away vital habitats that are homes to wildlife.

His second, Dead Zone, explores the global impact of industrial animal agriculture on wild animals and birds. For example, the critically endangered Sumatran elephant, orang-utans, and tigers live in the tropical rain forests of Sumatra, one of the islands of western Indonesia. Sumatra is also, where oil palm grows. Its fruit produces palm oil. One of its by-products is added to the feed fed to factory-farmed animals. To supply this trade, Sumatran tropical rain forests are cleared to intensively grow oil palms. Consequently, the jungle—home to elephants, orang-utans, and tigers—disappears at an alarming rate.

Further to the issues raised by industrial agriculture, including its impact on wildlife, is the harm it causes to the soil. Our ability to stop climate emergency and improve soil health are vital to ensuring the planet’s well-being and our survival. In Sixty Harvest Left, Philip describes how intensive crop production to feed farmed animals removed from the land to industrial confinement depletes the soil. He also reports the UN’s statement that ‘if we carry on as we are, there could be just sixty harvests left in the world’s soils’.

Industrial agriculture may have provided us with cheap food in a lifetime. But at what cost? We only have a lifetime to turn around present agricultural systems to address climate emergency and invest in the soil for future harvests. Societal change is required to refocus industrial agriculture away from chemical-dependent, intensive factory farming. ‘Switching to soil-enhancing regenerative and agro-ecological farming,’ Philip advises, ‘using techniques that replenish soil fertility and capture carbon along the way’.

At an individual level, I interpret Philip’s advice as a call to go vegan. Boycotting animal products and ingredients reduces the consumer demand for them. To transition to vegan, try plant-based meat and cultivated meat products. If you feel you must eat meat, eggs, and dairy, only buy them from proven authenticated sources where the animals live free-range and drug-free. Add your voice as a newly minted vegan for the systemic changes we need to how food is produced.

Read books. Change the world.

This is the first in a series of four posts adapted from their first publication on The British Library’s Social Science blog in 2023. The four posts in this series focus on ‘Animals and Climate Change’, ‘Animals and Feminism’, ‘Animals and the Law’, and ‘Animals and Social Justice’. In 2022, The British Library acquired the Kim Stallwood Archive, publicly available for research.

Carson, R. (1999) Silent Spring, London: Penguin Book

Harrison, R. (1964) Animal machines: the new factory farming industry, London: Vincent Stuart

Lymbery, P. (2017) Dead Zone: where the wild things were, London: Bloomsbury

Lymbery, P., Oakeshott I. (2014) Farmageddon: the true cost of cheap meat, London: Bloomsbury

Lymbery, P. (2022) Sixty Harvests Left: how to reach a nature-friendly future, London: Bloomsbury

Silverthorn, E. (2023) Roaming Wild: The Founding of Compassion In World Farming, Caithness, Scotland: Whittles Publishing

Please let me know which books you recommend reading about animals and climate emergency. Here are some to prompt you:

Food, Justice, and Animals: Feeding the World Respectfully by Dr Josh Milburn, OUP (2023)

Regenesis: Feeding the World without Devouring the Planet by George Monbiot, Allen Lane (2022)

The Meat Paradox: Eating, Empathy and the Future of Meat by Rob Percival, Little, Brown (2022)

The Garden of Vegan: How Plants Can Save the Animals, the Planet and Our Health by Cleve West, Pimpernel Press (2020). Read my interview with Cleve West.

Read Books--Change the World! Good slogan. Thanks for another informative column.

What do you think of Robert Goodland and Jeff Anhang's climate report? It claims that industrial animal agriculture is 51% responsible for global warming. In this case, it is no longer an effect but the main cause of global warming.