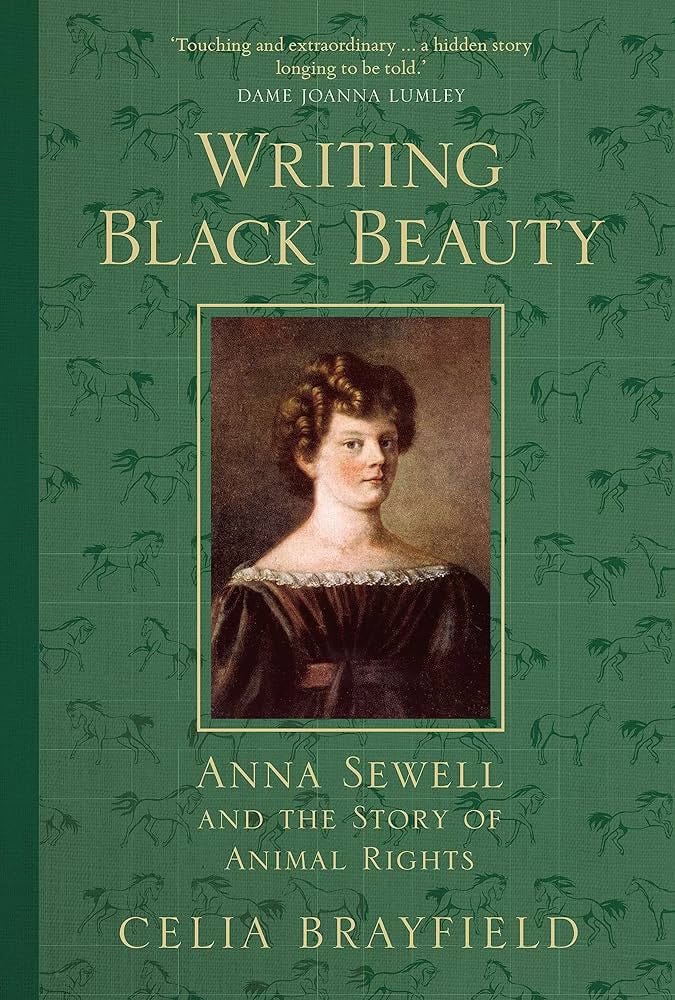

Welcome to the eighth in a series of interviews with authors. Celia Brayfield is a multi-award-winning novelist, journalist and critic. She is the author of nine novels ranging from modern social fiction to international bestsellers.

When you were growing up did you have cats, dogs, and horses or other companion animals who shared your home? Were you always someone who felt compassionately toward animals?

I grew up in a North London suburb where we had a dog, and then later a cat. I'm a cat person and have always had cats ever since. We also had chickens and pet rabbits, quite a little farm for a semi-detached suburban villa. Horses were a wonderful romantic dream. I had a dashing cousin who had his horses and occasionally let me hold one in their stable yard. Some of my school friends went riding on weekends and were crazed horse girls. I was incredibly envious of them. My parents were terrified of the cost of riding lessons and almost as afraid of horse riding as an upper-class sport. Although they let me go for pony rides on holiday, they were dead against anything more than that. I think parental opposition is probably the greatest motivator a person can have. Naturally, as soon as I left home, I looked around for a riding school and learned to ride. I think riding is such a wonderful pleasure, and such a great way of teaching children to be responsible for an animal, to develop physical courage and to work with an animal in a relationship of respect. So, when I became a mother myself, I looked for a riding school for my daughter when she was old enough, and discovered the Wormwood Scrubs Pony Centre in West London, an urban riding centre which subsidises riding for the disabled by offering riding lessons. It was founded by a nun, Sister Mary Joy Langdon, to whom Writing Black Beauty is dedicated. She is one of the most impressive people I've ever met.

How did you discover Black Beauty? Do you recall the first impression it made on you?

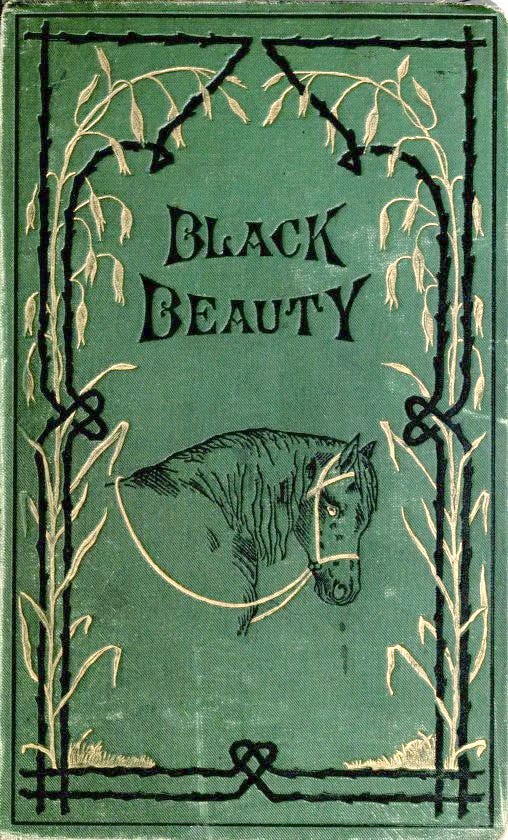

Black Beauty is a classic book for animal-loving children, although it was written for young adult men, the tearaways at the reform school which Anna Sewell's family founded near Norwich. However, my parents didn't want me to read it, not only because it was about horses but also because it was a very moving book, and I was a very sensitive child. We never went to see Bambi. So, I discovered it as an adult, a red-leather-bound book I found in a second-hand bookshop. I think I read it in one sitting. The amazing thing is that Beauty just seems like a real character, and you stay up all night reading and hoping things will work out for him. Later, I realised how important it was in literary terms, an anthropomorphic novel which sets out to create the animal's point of view, rather than giving human attributes to an animal. Then I realised that popular fiction is much more influential in social terms than literary fiction, and I started researching a range of best-selling novels with enormous social impact for an academic book. Black Beauty was top of the list. Anna Sewell's great achievement was to write a moving but very simple book that connected with ordinary people and made them think about the welfare of the animals on whom, in the late nineteenth century, their lives depended. As the RSPCA eventually acknowledged, Black Beauty broke through the class divide that stopped the animal welfare movement from becoming mainstream because it was seen as a moral crusade by out-of-touch upper-class people.

You have an impressive career as a journalist with The Times and a successful career as a novelist and writer of nonfiction. Have you always wanted to write about animals? Is your biography of Anna Sewell the first opportunity to do so? Do you have plans to write about animals?

You should ask my former colleague, Celia Haddon, who was for many years the animal writer at the Daily Telegraph! I would not have dreamed of trespassing on her turf. But to be honest, I'm a little wary of the tendency in the popular press to sentimentalise animals and jump on one bandwagon after another. The exploitative nature of most of our newspapers repels me and I just didn't want to go there. There is a morbid fascination with foxhunting which I think has been tragically divisive in setting rural and urban communities against each other. I think rural communities feel marginalised now. I satirised this in my last novel, Wild Weekend, in which a New Labour minister goes off to a Suffolk village on a mini break with her daughter. It's full of gentlemen farmers, old-fashioned farmers, urban fox rescuers and activists who liberate bees. The plot is based on William Goldsmith's play She Stoops to Conquer. It's probably my best book although my publisher refused to back it.

What compelled you to write Writing Black Beauty?

I wanted to honour the memory of an ordinary disabled woman who gave her best to her community throughout her life, who quietly lived by her Christian principles and who left a legacy in establishing animal welfare as a mainstream value. Anna Sewell was left disabled in her early teens by a simple, everyday accident. She fell as she ran home from school. Nowadays she'd have been diagnosed with a broken ankle and recovered fully, but in the nineteenth century, before X-rays, she was left in constant pain and mostly unable to walk. A terrible depression took over her for most of her twenties. But she could ride a side saddle, and drive a pony trap, and they were lifesaving things that helped her work as a teacher and even set up a free school in a small mining village just outside Bath. Her mother became a bestselling author of popular verse novels in her sixties. Anna worked with her as her editor. She gained huge experience in her own home of communicating with ordinary people who, in those days, were often illiterate or semi-literate and relied on having books read aloud. Eventually, she became terminally ill and, instead of giving up on life, decided to write her book with the simple aim of "inducing kindness to animals," which it certainly has done for almost 150 years.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to write about animals?

Well! Don't be a print journalist! Print journalism is in a death spiral all over the world. I'd advise them to gain knowledge, study, follow science, work with animals, and put their writing skills to use working for animal charities. See where your heart takes you. Then if it's right for you, think about connecting with people online, podcasting, making videos for TikTok or YouTube, or working for an online news source. The most influential animal activists in the media are people like Clare Balding or Chris Packham. If you are set on a media career aim for TV, but be aware that, although wildlife television is hugely popular, counting worldwide audiences in billions, responsible documentaries talking about animal welfare or climate change are less popular and you may have to be highly strategic in communicating your message. Also, the arts and the media are very highly competitive environments so start NOW building work experience, making connections, and researching the career path that will be right for you.

As you wrote the biography, did you reflect on the contemporary animal rights movement and compare it to the movement in Anna Sewell’s time? If so what similarities and differences did you notice?

This is such a fascinating question. In researching Writing Black Beauty I quickly discovered that the early history of the animal rights movement, in both Britain and America, was very much two steps forward, one step back. Or even two steps back. It took more than twenty years of campaigning inside and outside Parliament to get the first bill banning animal cruelty through Parliament, The Cruel Treatment of Cattle Act of 1822, the first animal welfare legislation in the world. It was very reluctantly enforced, and the organization that became the RSPCA was set up two years later. It promptly went bust and most of the activists either went to jail or had to flee the country. Queen Victoria's patronage helped restore its fortunes. But it was dogged by antisemitism, misogyny, and class divisions. Some of the most effective animal welfare campaigners were women but in Britain, the RSPCA just marginalised them, except of course the millionaire philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts, whose money was welcome but who wasn't encouraged to make any strategic contribution. But, factionalism and infighting, when people feel so passionately about a cause, is just tragic and I'm afraid I can't see much change.

One thing that was very clear to me as I researched the book was the decisive influence Queen Victoria and Prince Albert had during their lifetimes. They were committed animal rights campaigners and led by example. The painter Edwin Landseer was also hugely influential in his anthropomorphic animal pictures, which were bestselling prints. Anna Sewell even copied some of them. So the right leadership is crucial, one or two prominent people can make a real difference and reaching hearts and minds is as important as getting legislation passed.

I didn’t know about Sewell’s injury! Interesting Q&A!