Melanie Challenger researches and writes on the history of ideas, especially the relationship of humans to the living world. In short, she says, natural philosophy best describes the focus of her work. Her latest book is How to Be Animal, and she recently edited the anthology Animal Dignity. She co-founded Animals in the Room to explore non-human life in policy and governance. She is a Vice President of the RSPCA.

How did you first become concerned about the natural world? Please describe the path that led you to become a researcher on the history of humanity and the natural world. How important are animals to you? Are you, for example, a vegan?

I always had a natural curiosity about nature and our place within nature. I remember most vividly, as a child, spending hours and hours poring over three Encyclopaedia Britannica books on planetary science and physical geography. I would read and re-read all the paragraphs about natural processes, how the planets formed, how weather systems worked, and how volcanoes evolved. I can still conjure in my mind the illustrations from these books of different systems. I was absolutely absorbed by this. We also had a huge A-Z of animals, and, again, I spent countless hours reading that. The book used codes if the animal was considered endangered by IUCN measures. So that book affected me deeply, as I internalised both the beauty and wonder and the tragedy of biodiversity loss.

Another key influence from my childhood was the Natural History Museum, to which my dad used to take me. Again, those visits were a blend of awe and despair. I just could not understand why we were destroying the living world. And so, I suppose I always had an ethical sensibility. As an example, I wrote to the RSPCA as a young child with my design for a cattery that considered the perspectives of cats, for which I received a little certificate. It still makes me smile all these years later that I’m now Vice President. But I was always obsessed with the wild too. I used to spend my Saturdays collecting free travel catalogues from the high street shops and cutting out the places I wanted to visit. I was and remain enamoured of the forces of nature.

I began my working life in the creative arts, however, I wanted to be a novelist, originally. I was always attempting to write books from a very young age. I got the Artist and Writers Yearbook out of the library when I couldn’t have been more than 14. I was sending my poems to the local newspaper when I was younger. So, there was always this vocational drive to write and craft books. I turned to the history of ideas in part out of frustration that I was always trying to shoe-horn philosophy and theory into my creative writing. It reached a point when I realised that I just needed to write directly about ideas, without having the tension of plot or character development.

This was the starting place for my professional life in nonfiction. As for my later work in animal welfare and ethics, those things emerged quite organically. My involvement in bioethics came about because I was writing on bioethical topics and joined the Nuffield Council board when the then-chair, John Archard, suggested I apply for a position. The RSPCA reached out because I have written about our relationship with other species.

But how do I live that in my personal life? I don’t have any companion animals, but I spend a lot of time observing other species as an amateur naturalist. I have lived in rural places for most of my life, and prefer to occupy rich, multispecies environments. And I make ethical choices. I was a vegetarian for many, many years. Then I cut out dairy. Then I began to try and source ethical vegan alternatives for shoes, sunglasses, handbags, etc. I do the best I can, although I’m not perfect. My carbon footprint is not what it could be. The traveller is still alive in me. But it’s a constant effort to do what I can to live respectfully with other species.

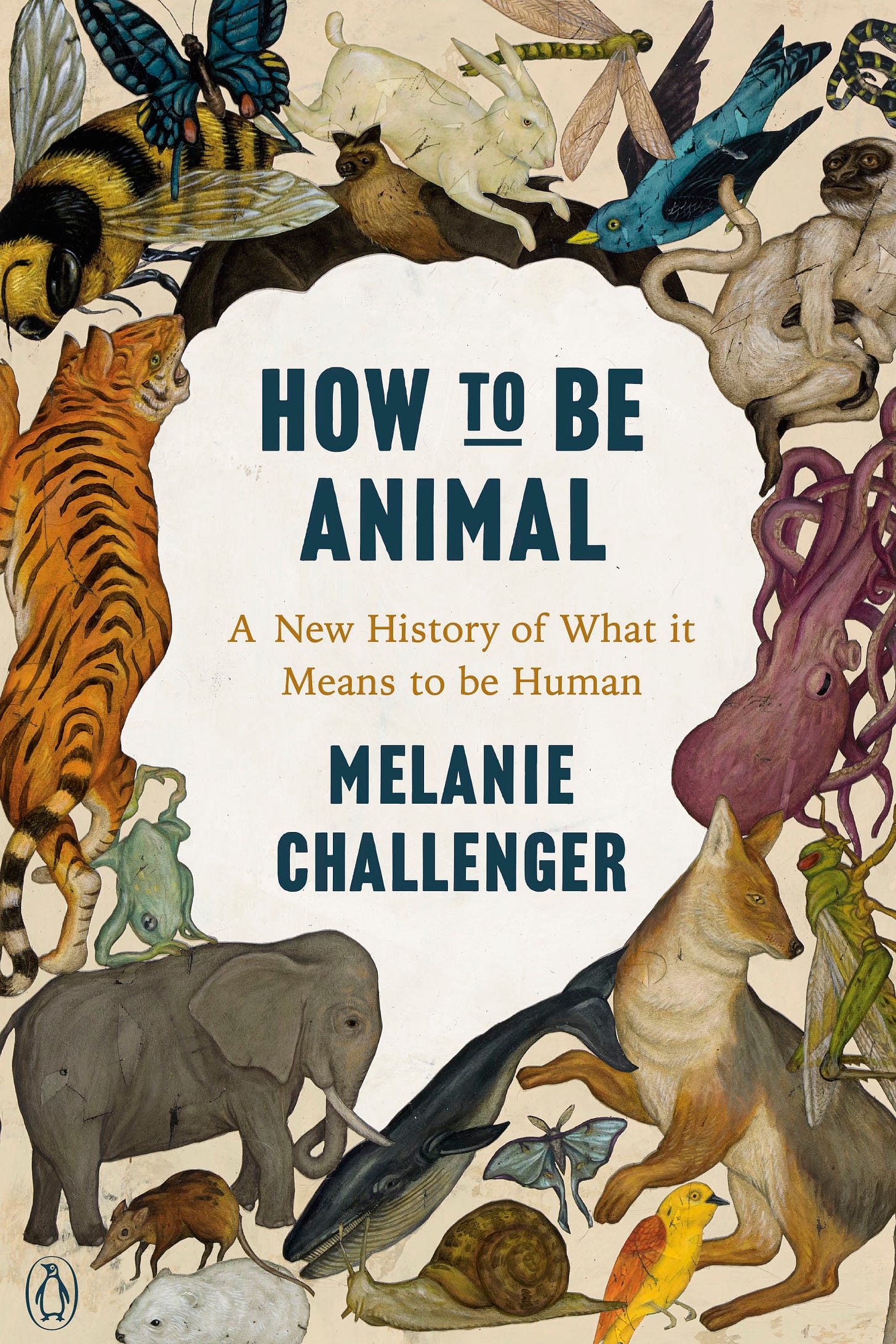

The subtitle of your latest book, How to Be Animal, is A New History of What It Means to Be Human. Please explain what this history is and why it is new.

Great question! There are no new ideas under the sun. What you often find if you work with ideas is that you think you’ve come up with some novel concept, and then you start researching and, before long, you find someone who was saying something like this two thousand years ago.

I came to the inquiry at the heart of the book through my reflections on how we have thought and talked about animality and nature across time and cultures. I was always intrigued by dualism, by this idea that we’re made of a bodily, animal bit, and a spiritual bit. Why is dualism so prevalent around the world? How does this affect the way we see ourselves and other species? This was the starting point for the book for me. What this then became is a history of how we’ve thought about being animals and how being animals affects us as humans, physically, psychologically, and morally.

So, for example, I look at the way our vulnerable mortal bodies can encourage us to reject the whole idea of animality as threatening and lead us to prioritize what we see as the non-animal parts of us. In turn, this can encourage a kind of human exceptionalism, whereby the most prized aspects of life are associated with those attributes we see as exclusively human and, in turn, the least “animal”. The subtitle was, in this sense, supposed to be a provocation. How can it be that our historical truth – that we are animals – is somehow also a novel idea to us? Yet, we do have to think in new ways about humanness as something that is fundamentally animal, physical, and mortal because we have spent such a long time in so many cultures telling ourselves that, at some level, we’re not animals. The further claim I make is that we can’t reconcile our relationship to the rest of nature unless we face our own animal being. And I argue that we will be happier, in the end, and better able to face life if we do.

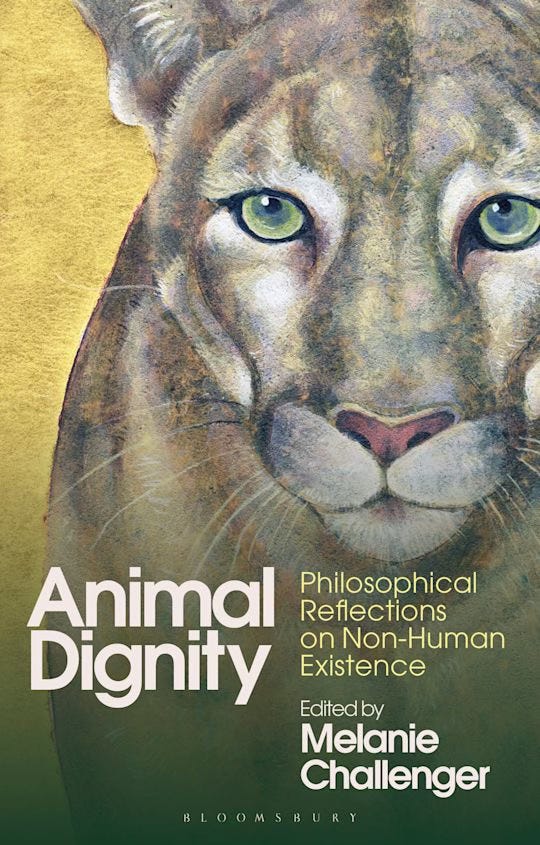

In the introduction to Animal Dignity: Philosophical Reflections on Non-Human Existence, you write dignity as a ‘modern concept belongs to moral philosophy and finds its place in practical branches of philosophy: ethics, particularly bioethics and medical ethics, and law and rights policy.’ What do you and your contributors understand animal dignity to mean? Did you agree to one definition?

Another great question. And not one I could have answered when we began the project. At the outset, I brought together scholars and authors whose work I admired and who had already written about or touched on the possibility of animal dignity. What didn’t yet exist, even though there’s scholarship on animal dignity, was a gathering together of this work into one volume. It felt, however, premature to impose a strict conception. The aim, instead, was to diversify the field and open it out for engagement and further scholarship. I sought to give an overview of the breadth of work and to invite a range of different views from the areas that dignity touches on, from law to religion, to practice.

It interested me that dignity is often characterized by its woolliness, and yet I was surprised by how much commonality there was across the authors. When it came to writing the interlinking sections between the chapters, I began to see that there were some elements to the definition and concept of animal dignity that were present in nearly all the entries. The first thing is that dignity isn’t a possession per se but a way of relating that emerges between biological beings who can be made vulnerable by dint of their unique lives and forms. The dignity of animals, human or otherwise, then is grounded in their qualities as living beings: agency, sentience, physical fragility, and expressiveness. To treat another with dignity is to give them respect, to honour them such that we don’t degrade them or harm them or humiliate them or leave them vulnerable to worse treatment. Dignity in all the conceptions has a lot to do with power relations, and, in that way, I think it’s a good concept to apply to our relations with nonhuman animals.

In 2023, you became a Vice President of the RSPCA. I wonder what your view is on the RSPCA Assured program, which, it states, is the “only assurance provider dedicated solely to animal welfare.” As you know, it has received considerable criticism recently. Also, you co-founded Animals in the Room to “explore non-human life in policy and governance.” Please elaborate on what this mission means and how it will impact the well-being of animals.

When news came to me of the Animal Rising report into the failings of the Assured program, I asked for a lot of feedback and information from the RSPCA. I wanted to know, for example, if the footage I could see was verified from RSPCA farms and exactly what I was looking at. I wanted to know what evidence there was that RSPCA Assured both answers to an immediate ethical imperative but without de-incentivising people from making alternative food choices. I also wanted to know what was being done in response.

I was given convincing data that without the scheme, the lives of those beings who are on our farms in the food systems that exist presently would be substantively worse. From an ethical perspective, then, the trade-off is between embedding welfare standards for those animals alive today in the system, and believing that their lives matter right now, and not legitimising that system such that we reduce the number of animals in our food systems.

Animal Rising wants RSPCA to advocate directly for a plant-based future. While in my experience it shares the goal of reducing the number of animals being farmed, the RSPCA isn’t a vegan activist organization. It exists to support the animals, wild or domesticated, that are vulnerable to cruelty and harm. There’s alignment, but the mission and function of the two organizations are not the same. So, there was a fundamental tension there, such that RSPCA couldn’t meet the objectives of Animal Rising.

I believe that was the right decision. There should be a range of different organizations that meet the diverse needs of nonhuman species. We shouldn’t all be reduced to the same mission. That said, there were positive lessons to be learned, and the small number of farms that were exploiting the scheme will serve now as a cautionary lesson, I hope, for any other businesses. It would also be my preference to alter the language and imagery around RSPCA Assured. I believe RSPCA will continue to work on this.

Animals in the Room is a nonprofit and research network that I’ve been working towards with my colleagues at various universities for around five years. We exist to research, design, deliver and evaluate new methods for including the interests of nonhuman species more substantively in our decision-making processes. The principle is that other animals can communicate their interests and should be included and represented in the decisions that will affect them beyond the light-touch inclusion that already exists.

The question is: how do we do this? How do we know what other animals want? How do we overcome our anxieties around anthropomorphism or, by contrast, anthropocentrism? How do we measure what a good outcome looks like and how do we meaningfully make present other living beings who can’t directly speak for themselves? Our mission is to experiment and stress test around all these questions.

You are not only a researcher and writer but also active with many projects. You are intimately aware of the institutionalised exploitation of animals and the climate crisis and its impact on all life on Earth. Are you optimistic or pessimistic about humanity’s ability to address these challenges?

I would say I’m an optimistic pessimist. In my early twenties, I worked on several projects around human conflicts. During that time, I did a lot of research in war archives and talked directly with individuals who’d been caught up in wars around the world. It shocked me then and continues to shock me that we state sanction violence towards people, devastating the lives of whole generations. Our species is capable of extraordinary proactive aggression. That said, we are less violent than we once were, taken as a whole. And that is despite the vast numbers of us that there are today compared to even a hundred years ago.

Society and opportunity, education and wellbeing, can act as powerful modifiers of our worst impulses. Perhaps the future holds the potential for modifiers that may also reduce our violence towards other species and the Earth itself. In this there is hope. But the greatest hurdle I believe we face when it comes to meeting those challenges and improving how we live in balance with the Earth and its systems is our denial of the agency and meaningfulness of the lives of other creatures.

We live in this vast delusion that humans are subjects and all other animals (barring maybe the dogs we live with) are objects. That mindset is used to justify just about everything we do. We drain the land or cut down trees because human needs are the only ones that matter. We cull animals that get in our way because they’re dumb and insensible, whereas humans are conscious and intentional. We use animals to test our medicines because their lives are meaningless and human lives have dignity. I could go on. In just about every underlying driver of climate change or biodiversity loss, there’s a choice that is ignored because other species have no direct moral or legal status anywhere in the world. We tell ourselves that they lack something that would give them status: consciousness, language, smartphones, theatres, and concepts of death. Over the years, I’ve heard every reason under the sun. None of it stacks up when subject to robust analysis.

The bottom line is that we kill the wild because we want to. And then we make up the reasons afterwards that allow us to exploit. So, while I’m pessimistic because I can see the challenges, I’m also quietly optimistic because we have never been better placed with the science and technological tools at our disposal, to challenge the delusions that support an exploitative mindset. However, of course, why should a better relationship with other species cause us to change tack when respect for our species can’t achieve this? Here, commentators might point to governance structures, economic ideologies, and so on. But I think we underestimate the psychological dimensions of the world we create. Challenging the human construct is far more revolutionary than altering capitalism.