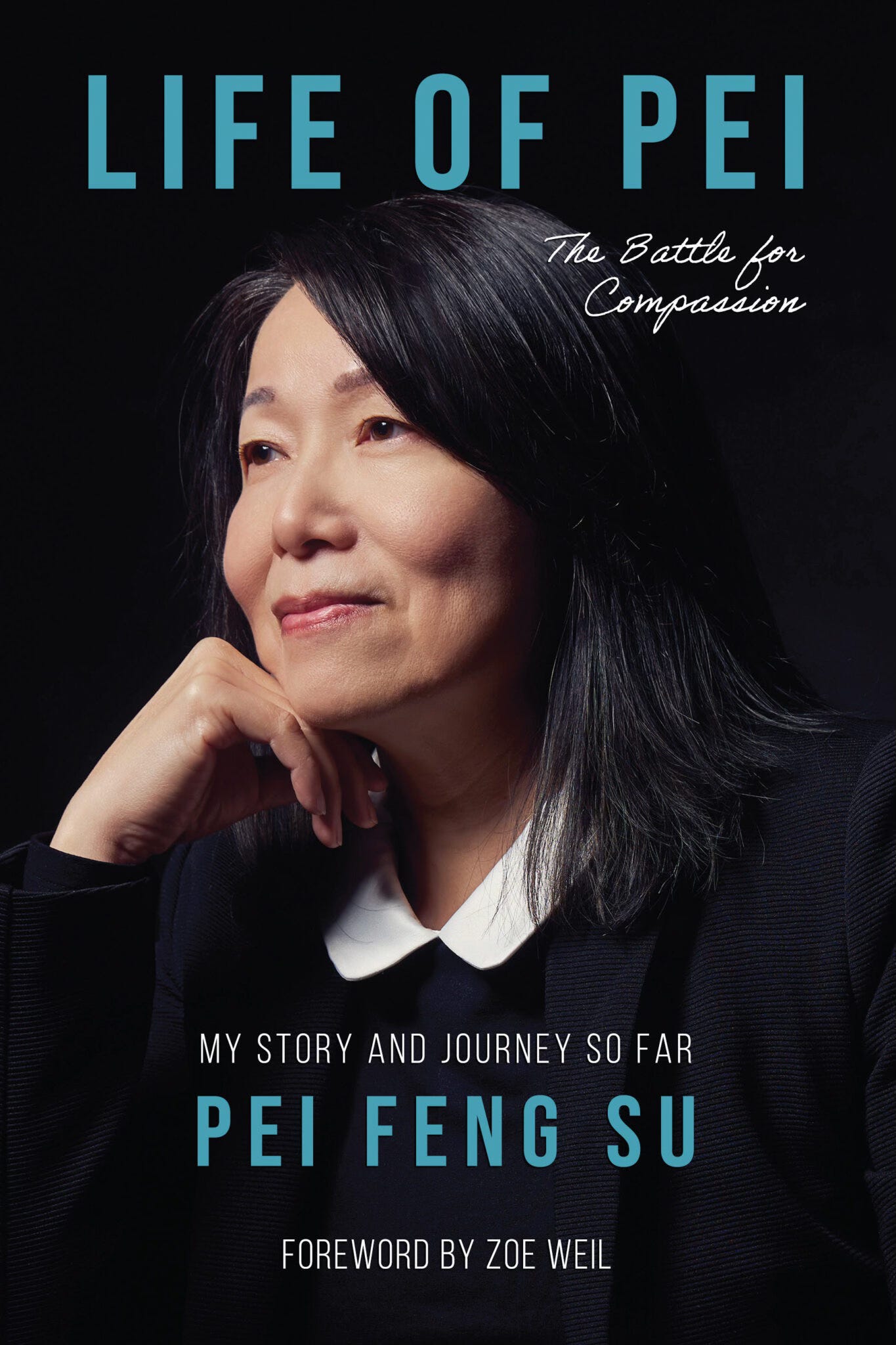

Life of Pei by Pei Feng Su

Author Interview

Pei Feng Su founded the nonprofit organisation ACTAsia in 2006 to promote kindness and compassion through educational initiatives in Asia. She is an international presenter at conferences, in the media, and a visiting lecturer at the Suzhou University in Shanghai. Her new book is Life of Pei: The Battle for Compassion (Lantern Publishing & Media; 2024). Welcome to the 24th in my series of interviews with authors of books about animal rights, veganism, and related issues.

In the Preface of your book, Life of Pei, you describe yourself as ‘two people in one body’. From a vulnerable latchkey kid and victim of sexual assault living in the last century in Taiwan to a wife, mother, and Founder and Chief Executive of ACTAsia in the United Kingdom. What were the key turning points that enabled you to live such a transformative life?

I endured a tough childhood. The passing of my parents, when I was still a young person, left me feeling angry and depressed. In my quest to understand the meaning of life, I began a lot of soul-searching. I explored several religions, but never quite felt that I fitted in until I found Buddhism. The Buddhist teaching—everything changes, nothing is permanent, and all life is equal—particularly resonated with me. Buddhism also helped me channel my anger and find inner peace. This enabled me to live the life I have and support the work I do.

Following my childhood trauma, I connected human injustice with animal suffering. The mistreatment of animals inspired me to be their advocate. In today’s world, I believe when one struggles with making sense of global and individual problems, religion provides support. Buddhism is more than a religion, however. Its teachings and philosophy are a way of life.

How did you become involved with the animal protection movement? Looking back on your experiences working with various organisations and their staff, what skills did you learn that helped you to establish ACTAsia?

My interest in Buddhism led me to become involved with a Buddhist Institute for three years, where I became a disciple of one of the female monks. During that time, I focussed on several issues including women’s rights, youth welfare, animal rights, and environmental degradation. My first animal campaign came about when we witnessed the cruelty inflicted on fish through hookfishing rather than by bait. It was cruel given the number of fish being hurt by hooking them.

I later worked with non-governmental organisations (NGO) in Taiwan where I was the first full-time staff member for the Life Conservationist Association, the first organisation to advocate for animal welfare and rights. I worked at the grassroots level on numerous issues including the inhumane killing of dogs, illegal wildlife trade, animals in entertainment, farmed animal issues—the list goes on.

To successfully advocate for animals and debate issues with government, media, and academics, I had to educate myself, as this was new territory. It was before the Internet and the World Wide Web. I had to glean most of the information from organisations in the US and the UK via fax machines!

With my grassroots experience, I was keen to learn more from large Western organisations. I joined World Animal Protection or the World Society for the Protection of Animals as it was then known. My time there taught me how to run campaigns and professionally manage projects. I learnt working for charities/NGOs is a ‘profession’ requiring specific knowledge and skills. Passion and emotion on their own were not enough. I also discovered the importance of sustainability and how to create campaign strategies, budgets, marketing plans, media campaigns, and so on. I had not learnt these things previously.

The valuable combination of experience at local and national levels gave me the foundation I needed to establish ACTAsia.

What were the main reasons for starting ACTAsia? What are you seeking to accomplish? What are the major challenges?

My experience with both grassroots and international organisations led me to see that there was a big gap in knowledge and understanding of what was needed at a local level. I felt strongly that large organisations did not always understand local issues and priorities, especially against a differing socio and political backdrop. For example, it is hard for large organisations to solve animal suffering in Asia, as they often do not appreciate that the local populations do not understand animal welfare and see animals as mere objects and resources.

The slogan bandied about by international organisations at the time, “Global Thinking, Local Action”, finally convinced me of the need to establish ACTAsia. To me, the slogan had a colonial feel and also a trace of propaganda. It felt like big Western organisations were telling the grassroots what to do. On the ground, however, the locals felt and thought very differently. At the time there was a big gap between international and local organisations and what they felt were the most critical issues. This difference of opinion prevails to this day.

I want to break the chains of this vicious circle by replacing constant firefighting with projects to effect change at the root cause. Today, we achieve this through ACTAsia’s work in education and training to educate and build knowledge and information. We empower people to make informed choices about animals, people, and the environment by cultivating change on the ground. ACTAsia works to drive decision-making that is no longer made from ignorance. For example, across Asia, animals are often viewed as a resource and the local population does not view them as sentient beings. Education is therefore critical and a necessary foundation to prevent animal cruelty and improve their welfare across Asia.

Our main challenge is a lack of funding. In the charity sector, large organisations have the resources to push fundraising. In comparison, whilst ACTAsia has a good working model and undertakes excellent work recognised by the UN, a lack of funding and resources restricts future growth.

The second main challenge is working in Asia. Working in China in particular, is very difficult due to tight restrictions imposed on charitable activities. Across Asia, as in all developing countries, charity work and its role are not as recognised as in developed countries. NGOs are often met with suspicion. As they are not well supported, the role of charities is limited. Locals often do not understand the need for charity work, as the sector is still relatively young

You have considerable professional experience with animal protection in Europe, the United States, and Asia. What are the similarities and differences between Western and Eastern countries regarding how animals are viewed and treated and the work of animal protection organisations?

Across Asia, animals are often viewed as objects or resources for human needs. In addition, companion animals and keeping pets as family members is a relatively new phenomenon. At the height of socialism in China during Chairman Mao’s era, pets were considered as bourgeois corrupt behaviour and banned. In the West, people are accustomed to living with companion animals and form strong bonds with them. When talking about animal sentience and animal rights in Asia, there is clearly a huge barrier to overcome.

The West is seen as far more progressive in terms of animal protection. The animal rights movement secured major successes in democracies, including the Constitutional Inclusion of Animal Rights in countries like Germany and Switzerland in 2000 and 2002. Another example of the West’s more progressive outlook on animals is New Zealand, which created ‘personhood’ as a specific legal protection for all primate species in 1999.

When I look at these progressive developments in animal law, I’m always amazed, as most countries in Asia do not even have an animal welfare or protection law within their statutes. This leads to no budget allocation from the government, and no infrastructure within the system to solve issues that need addressing. For example, when we try to tackle the factory farming issue, very often, no government accepts responsibility for the animals’ welfare. The department that deals with farmed animals is usually the agricultural department, which uses animals itself and is unlikely to restrict or change what it does.

People in both Eastern and Western countries can show kindness and compassion to animals, but it is generally harder for people in Asian and developing countries to show how much they care for them. Animals are viewed differently due to a lack of education and general ignorance. There might be more overt animal cruelty in Asia, but this is not because Asians are more cruel than Westerners. In my years of observation, much of the cruelty is caused by ignorance.

In the Western world, organisations are more mature, and their development over time has led to a diverse and rich movement. There are different kinds of organisations addressing different issues, including those that focus on greyhound racing or badger protection, for example. Some groups focus on specific areas of work through different disciplines, such as helping animals through legal aid. In Asia, most animal protection organisations focus on the welfare of dogs and cats. The percentage is relatively small for organisations working on non-companion animal issues. In the West, organisations are far more professional, having the resources to employ paid staff and look after them better. Staff working in the charity world are viewed as professionals in the West, whereas in Asia, charity work is not considered a proper job and so is less supported.

You have spent your career fighting injustice. What about sexism? Racism? How would you rank the progress made so far toward gender and racial equality? Generally, what are the key factors that drive you in this challenging work?

Being a minority female, I understand and feel close to the issues of sexism and racism. I have certainly encountered these issues, which have been more pronounced in my role as a female minority leader. Despite the UN's sustainable goals and policies to try and combat these problems across the globe, these issues still exist.

I feel that although sexism and racism still exist in the West, they appear in more sophisticated ways, and there are systems in place attempting to address them. In contrast, in Asia, sexism is perhaps more visible. Inequality between gender and race is more easily seen. I would say that gender and race equality issues have less awareness in Asia.

I’m often asked what are the key factors that drive me, especially after my cancer diagnosis.

First, I genuinely believe in what I do. Without this belief, it would be very hard to carry on through difficult times. The challenges are frequent (daily!) and continuous. Many people, I believe, find our work impossible as it requires an unshakeable belief. We must take a long-term approach to bring about positive change. Sadly, there is no quick fix for creating social justice.

Secondly, I feel very blessed to have the ability to visualise and see the path to create change. I see what things could be like in the future. I did not appreciate this gift fully when I was younger, but with time and experience, I have come to recognise it and be grateful. I feel I must trust my ability and do something meaningful with it.

Lastly, because of my vision and ability to see the way forward, I manage to successfully navigate my path through continuous obstacles. I do sometimes get stuck but always find some way forward.

I have hope. I believe that nothing is impossible, which makes me determined to bring about positive change, despite the journey being hard. At my age, I no longer suffer from self-doubt and feel that I can successfully bring about social justice for all.

If one day, it became necessary to close ACTAsia, perhaps due to a lack of funding, then I would have no regrets. I believe in my work and would strive to carry on in some other way.

Thank you.