Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936) was a Russian scientist who experimented with dogs in his laboratory, the Institute of Experimental Medicine, in St Petersburg. The phrase, “Pavlov’s Dogs,” is usually associated with the image of dogs salivating in response to a bell. He claimed his research showed how animals can be conditioned to associate certain stimuli with specific responses. In addition to the sound of a bell ringing, Pavlov subjected dogs to electric shocks and various stimuli such as the ticking of a metronome, an extremely loud buzzer, and various homemade devices designed to inflict pain. The dogs were strays taken from the streets of St Petersburg.

One hundred years later, it’s estimated that 58.3 million animals are used in research throughout the world. The most researched animals are mice and rats but also used are nonhuman primates, guinea pigs, rabbits, birds, cats, ferrets, and dogs. The purposes of the research include fundamental biological research, product development and safety testing for human and veterinary medicine, disease diagnosis, and education and training.1

“Unfortunately, the laws that currently cover animal welfare are clearly inadequate and, in some cases, ridiculous,” notes Richard J Miller in The Rise and Fall of Animal Experimentation (OUP; 2023). For example, the US Animal Welfare Act excludes the species most used in research (rats, mice, birds).

The challenge throughout the history of the anti-vivisection and animal rights movements has been how to frame and present the animals’ plight in ways that increase the public’s willingness to learn about something they’d rather not think about even though the research is claimed to be done in their name as consumers of products and services.

Now and then I discover innovative ways that make the case for animals that move and excite me. I see this increasingly less from the animal rights movement and more from the arts. Often, these are creative moments such as reading a book (my favourite animal rights novel is A Tiger for Malgudi by R. K. Narayan); discovering an artist (the visual journalist Sue Coe is another all-time favourite); and watching a film—you must watch Umberto D. by the Italian director Vittorio De Sica.

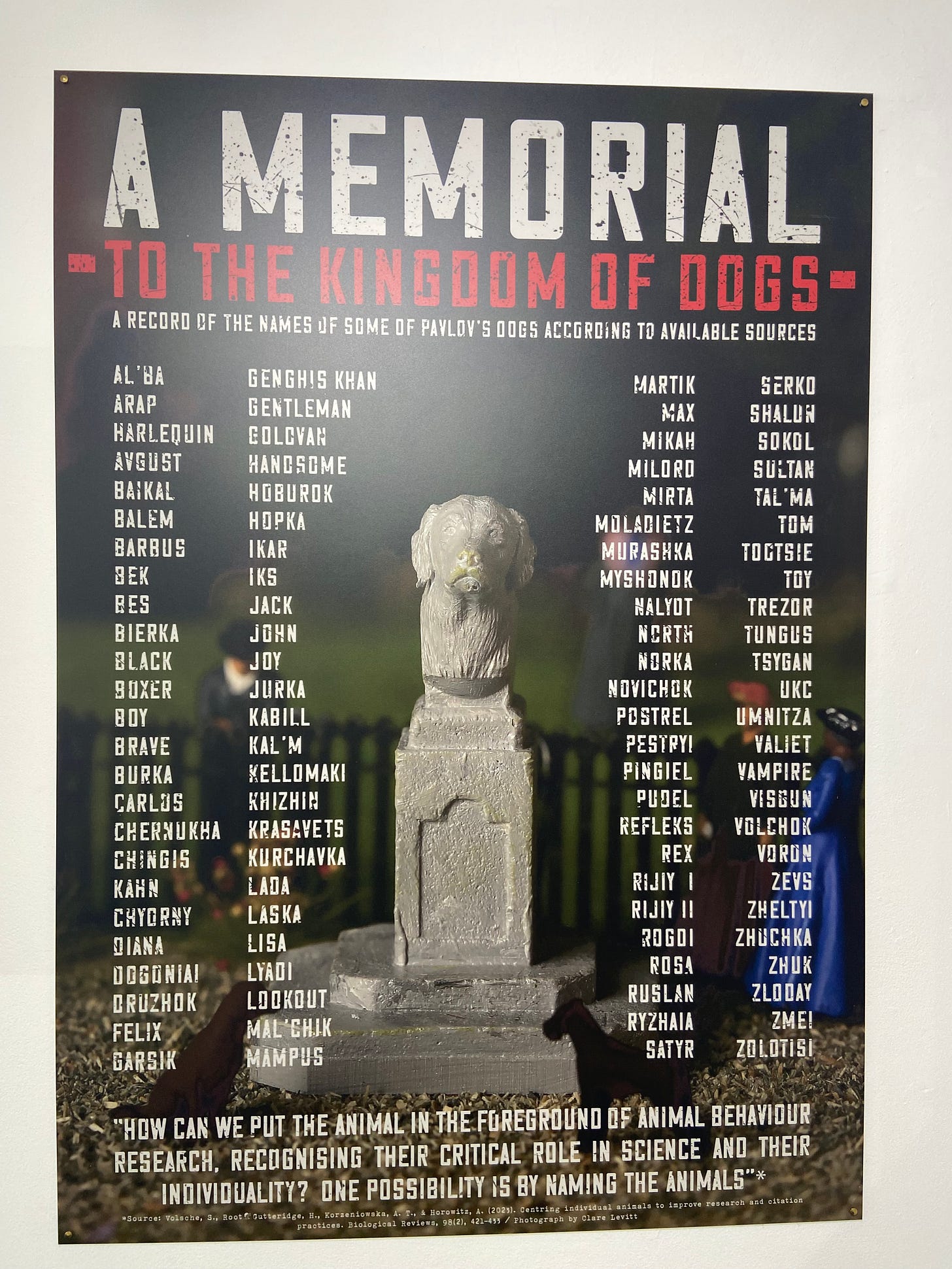

The most recent example of a creative moment for animals is the Pavlov and the Kingdom of Dogs exhibit by Matt Adams and Jim Wilson at the 35 North Gallery in Brighton until June 7. Matt is a Principal Lecturer in Psychology at the School of Humanities and Social Science. Jim is a Technical Project Manager for the School of Art and Media. They both work at the University of Brighton. The exhibit is part of a larger project about Pavlov and his dogs that’s funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. The first thing I noticed was how Matt and Jim placed the dogs centre-stage throughout the exhibit.

I appreciate not everyone can get to see this in the coming weeks. Run don’t walk if you can. This is why I met with Matt and Jim recently to discuss their exhibit and produce two short films of them talking about two of their exhibits. Please forgive my amateur filmmaking.

In the first, Matt and Jim talk about “Bandit! Barbarian.” This is a diorama of an imagined situation involving an anti-vivisection protest where the protestors attempt to pull down a statute of Pavlov.

In the grounds of the Institute of Experimental Medicine in St Petersburg there stands a stone monument dedicated to the laboratory dog. It was built at Pavlov’s request and includes various inscriptions that describe the ‘sacrifice’ of dogs to science as noble and necessary, emphasise the dogs’ ‘joy’ in their service to the experimenter, the ‘dignity’ of their treatment, and the avoidance of any ‘unnecessary torment’.

In the second film, Matt and Jim describe “The Physiology Department.” This is a combined model of Pavlov’s desk on top of a doll’s house reimagined as his laboratory. On Pavlov’s desk is an “open book [that] imagines a catalogue listing some of the various stimuli available for conditioning experiments.” Below is the laboratory showing Pavlov watching an experiment with a dog and rows of dogs in the ‘gastric juice factory’.

Pavlov’s experiments were funded in part by the public sale of the gastric juice of dogs as a cure for chronic indigestion in humans. While most dogs were destined for the labs and experiments, some were designated the role of ‘factory workers’ for this purpose.

I plan to stay in touch with Matt and Jim and help them in any way that I can to get more people to see Pavlov and the Kingdom of Dogs. Meanwhile, here are some more photos of the exhibit.

See also:

Pavlov and the Kingdom of Dogs

University collaboration makes Pavlov’s dogs the tiny stars of a new exhibition

See The Costs and Benefits of Animal Experiments by Andrew Knight (Palgrave Macmillan; 2011)

This is great!! Never thought of an art exhibit before. A lot of people will see it. It's true, people don't want to think about animal suffering. They'll even tell you that out loud.

Fascinating. I really don't know much about Pavlov, but the battle to get dogs out of research continues to be raged. The public has no idea. Still!